Let’s pick up where we left off

Last post about the Time Value of Money almost got out of hand and developed into a much longer post than I planned. And we didn’t even cover everything there is!

But no worries, here is the part 2.

We covered basic information about inflation, risk-free rates, and a bit about discounting. But we still didn’t quite get to where these concepts come together. This time, we’re going to look into Net Present Value, where we use discounting, and how to calculate our real returns from bonds after taking inflation into account. Let’s go!

Real rate of interest

Inflation should be taken into account in every type of investment, but it is perhaps easier to conceptualize with bond investments because of their nature of being risk-free and having guaranteed returns. It is important to understand that there is generally always inflation, so every annual return needs to be analyzed and compared to inflation rates.

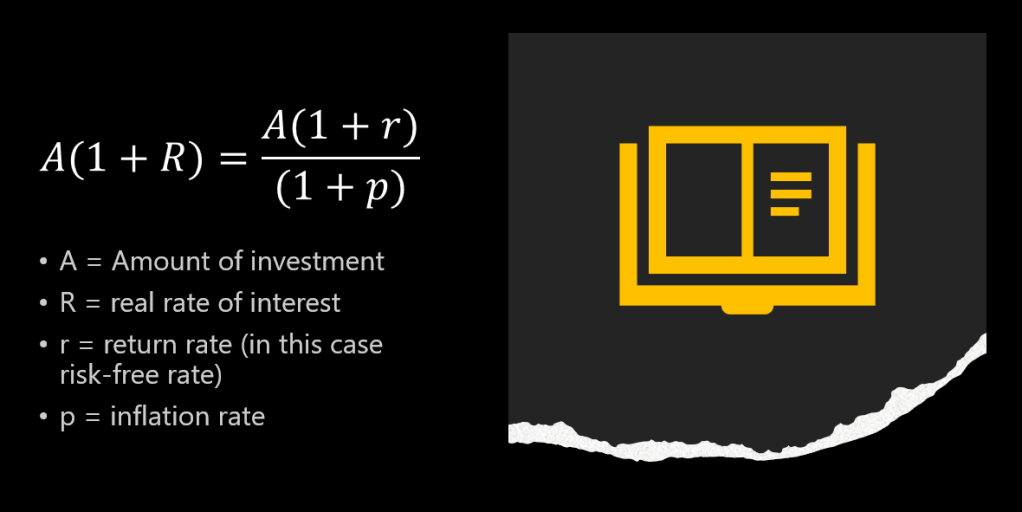

Let’s take an easy example. You have bought some 1-year bonds with a rate of 6%, and during that year, inflation is 3%. Your investment increased by 6%, but at the same time inflation lowered it’s worth by 3%. How do you calculate this? Your invested amount is again described as A, and in this example, it’s $1000. Inflation is p and return rate is r. So, after the return from the bonds, your investment would be

A * (1+r) = $1,000 * 1.06 = $1,060.

Then, as you learned last time, inflation is taken into account by dividing the amount.

A * (1+r) / (1+p) = $1,060 / 1.03 = $1,029.13.

You can on put the real rate of interest (R) into the following formula:

1+R = (1+r) / (1+p),

which can be simplified to

R = (1+r) / (1+p) – 1.

In the previous example, the real rate of interest was

1.06 / 1.03 – 1 = 2.913 %.

As you can see, $1,000 * 1.02913 = $1,029.13, as calculated earlier. In a healthy economic situation, the real rate of interest should always be positive, since investors demand that risk-free rates and their real returns are higher than inflation.

You may have come across situations, where the real rate of interest has been calculated with the simplified formula R = r – p. This is used quite often, because it’s much simpler to calculate, and with low interest rates the result is close enough with the exact rate (as in the example 2,913% vs 3%). However with higher inflation rates, this simplified version could lead to greater mistakes.

In the late 2010s, there were situations where the real rate of interest was negative, mainly because central banks wanted to revive the economy by lowering their rates. But that’s a whole other story. In short, real rate of interest is the amount that your investment really grows. This is also why you should invest to battle the inflation. If you don’t, your real rate of interest is negative.

NPV and discounting

In the previous post, we talked about how you would ‘lose’ money by keeping it in your bank account because you could be investing it risk-free in government bonds. Companies are usually very efficient in this. They are always looking for investments better than risk-free bonds because that’s like the benchmark level they would surely get. If there is nothing else, then bonds are the minimum investment for their money. Keeping it in the bank is not a good option. Of course, they also need money constantly to keep up with their operations and daily expenses, but now we are talking about the extra money they can invest or pay as dividends.

Let’s go through this with a very simple example. Company A is considering buying an apartment building that, according to their estimations, could be sold after a year with a 5% return. Their other option is to invest the same amount into risk-free 1-year bonds that are currently at 5%. Both options offer the exact same return, but one is risk-free and the other is based on estimation with several risks. Which one would you choose? I hope you answered the risk-free bond.

How does this work with numbers, then? Let’s do the previous example with numbers, but this time let’s assume that the apartment building would return 9% to better reflect the risk. So, we have two options to invest $1,000,000:

option 1 is a 1-year bond with a rate of 5%

option 2 is to buy the apartment building with an expected return of 9%.

This is where discounting comes into play, so let’s take a minute to figure out what it is.

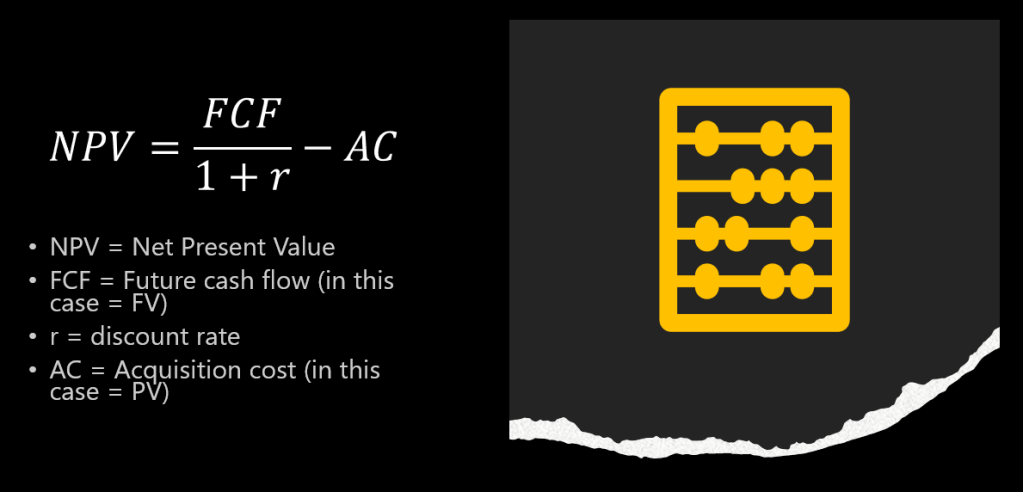

You can think of discounting as the opposite of compounding. If you invest $1,000 (PV) at a 4% rate (r), you will have $1,040 (FV) after a certain time period. So, you are calculating the future value (FV) of your investment while knowing the present value (PV) and interest rate (r). Discounting is about calculating present value while already knowing the future value and interest rate.

Now we finally bring in the numbers. Let’s begin with option 2 (you’ll soon figure out why). We can easily calculate that with a 9% return rate, the Future Value of option 2 would be $1,090,000. Now we discount it using the risk-free rate of 5%. We will get

$1,090,000 / 1.05 = $1,038,095.24.

Now we will calculate the Net Present Value (NPV) of option 2 by subtracting the Present Value (which is here the acquisition cost) from the discounted Future Value. We get the following formula:

NPV = FV / (1+r) – PV = $1,038,095.24 – $1,000,000 = $38,095.24.

If the result is positive, the investment is profitable. If you would like to see more of these types of examples, check out my Learning post about NPV.

NPV is basically comparing the return from option 2 to investing in 5% risk-free bonds, which in this case is option 1. It also means that you would need to invest $1,038,095.24 in those risk-free bonds to get the same Future Value as you would from investing $1,000,000 into that apartment building with a 9% return. The acquisition cost is the cost incurred at the beginning of an investment. In this case, it is the purchase of the bonds or the amount of money invested in the construction of the apartment building.

If the result of the NPV is positive, then in this case, option 2 is better than option 1, and vice versa. That’s also why we didn’t calculate option 1, because it would have resulted in $0, as we would have compared it with itself. Of course, in this simple calculation, we could say directly from the beginning that option 2 would be better, but when there are cash flows from several years, it wouldn’t be that easy to estimate without calculations.

That’s it about these themes! In the next Investing post, we are going to talk more about bond markets, which we have already covered a little. Thanks for reading, and I hope you found this post interesting! See you next time!

Leave a comment